From the Main-Danube Canal to the Isental freeway, from the Franconian Lake District to the airport in Erdinger Moos, from the Bavarian Forest National Park to the boomtown of Regensburg: the Free State of Bavaria has undergone extensive modernization and changed its face in recent decades.

All in all: construction, reconstruction, expansion wherever you look. Some rejoice at the progress, others complain about the destruction of nature. Today, it is hard to imagine our affluent society without many things. The HdBG presents the projects with pros and cons without committing itself. It sees its task as providing a basis for discussion. At the end of the exhibition, visitors can try to find out for themselves how major projects should be tackled in future and what needs to be taken into account.

The exhibition itself is staged as a construction site and presents itself as a media spectacle: a 50-metre projection screen transforms the museum's Danube Hall into a panoramic cinema. Activity stations, research terminals and digital games turn the visit into an interactive experience.

Of reconstruction and planning euphoria

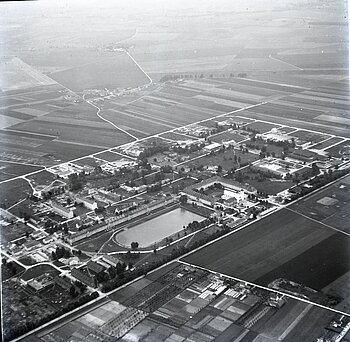

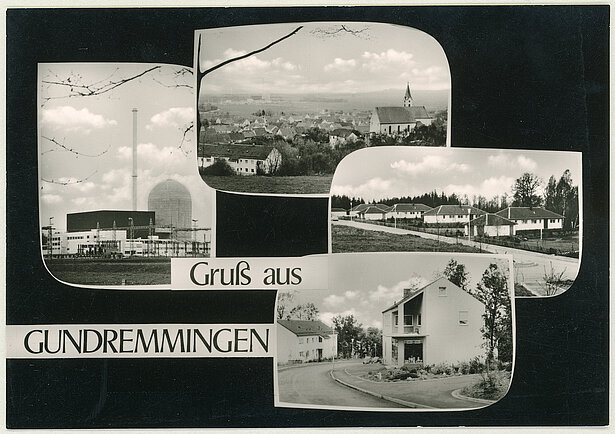

The exhibition begins in the post-war period: Many Bavarian towns lie in ruins, almost two million displaced persons and refugees arrive in Bavaria and need work and accommodation. With displaced persons towns such as Traunreut, Waldkraiburg and Neutraubling, completely new places are created on former military sites and airfields. The economic miracle and planning euphoria soon set the pace in the Free State. Major projects such as the Main-Danube Canal and Germany's first commercial nuclear power plant in the Swabian town of Gundremmingen were built. Since the 1970s, monument, environmental and nature conservationists have taken an increasingly critical view of the major construction projects.

Tourism, energy and mobility

Germany's first national park was established in the Bavarian Forest in 1970 and was fiercely contested for a long time, partly due to the bark beetle raging there, while the Franconian Lake District is one of the less controversial projects. Both regions now attract numerous tourists and enjoy broad support. Building in the Bavarian (pre)Alps has long been a tightrope walk. Year-round, climate-friendly and sustainable offers have increasingly been declared a goal in recent years.

A final assessment of many construction projects and large-scale projects is neither easy nor clear-cut, as an example from Swabia shows: On the one hand, the Lech, once the wildest of the Bavarian Alpine rivers, serves as a reliable supplier of renewable andCO2-neutral energy with its 30 or so hydroelectric power plants. On the other hand, its ecological status is only rated as "moderate" due to the damage caused to flora and fauna by barrages and flood control structures.

In addition to energy production, many large-scale projects are aimed at increasing mobility. Due to the increasing volume of traffic, the road network in Bavaria is being further expanded. One of the most controversial routes is the Isental highway. A decades-long conflict, including legal disputes, accompanied the construction of the A94 section. The situation in Erdinger Moos was different: in the 1960s, there was little doubt about the need for a new major airport for Munich. Inaugurated in 1992, the airport soon develops into an economic engine and is constantly expanded.

Invigorating construction boom in Regensburg

There have been heated controversies about the development of Bavaria's cities since the end of the war. Should old buildings be preserved or make way for new buildings and traffic routes? In the 1960s, several streetcar lines had to make way for the growing car traffic.

The Bavarian exhibition illustrates the path from structurally weak problem child to "boomtown" using the example of Regensburg, where a city highway and many other construction projects were prevented despite some interventions in the historic cityscape.